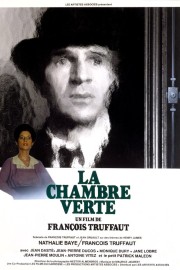

The Green Room

For the past two years I’ve found myself reviewing movies from Jean-Luc Godard, the still living titan of the French New Wave. This year, I finally arrive at a film from that other pillar of the New Wave– Francois Truffaut. Like Godard, I am too unfamiliar with his work, but in time I will be familiarizing myself with as much of his work as I can. Most Americans are perhaps best familiar with Truffaut with his cameo in Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” A year after that, he would be on screen again in his own film “The Green Room,” which I watched for the first time today.

Truffaut’s 1978 film (which also goes by the title “Vanishing Fiancee”) begins with a montage of blue filtered stock footage from the trenches of WWI as the credits roll; as he was often known for, Truffaut is paying homage to the history of film by giving the footage the look and feel of the old silent films from the early days of cinema. Next we see Truffaut (whom we have seen in uniform in shots during the credits) as his character, Davenne, attends the funeral of his friend’s wife; Davenne’s own wife has passed away as well. Those loss coupled with the friends he lost in the trenches has led to his deep obsession with mortality. Living in a small town with his Governess and a young deaf boy named George, Davenne writes obituaries and collects artifacts that remind him of those he has lost, bringing him into close proximity to a woman (Nathalie Baye) who has also lost loved ones around her.

Truffaut’s haunting film deals with a fundamental question of life: How can we best honor the dead? If we lose a loved one, is it right to move on, or should we hold on to that love forever? If a friend whom we have had a falling out with passes, is it right to drudge up the past and bring up their failings? What’s the best way to preserve a loved ones memory– by building a shrine to them, or by living how they would want us to live? Truffaut poses and explores these questions in a film, which he cowrote with Jean Gruault based on the works of Henry James, that has the delicacy and bold directness of Tarkovsky and Bergman. Gone is the youthful irreverence of “The 400 Blows” and “Shoot the Piano Player” as Truffaut looks at life and death, the living and the dead, with honesty and sorrow. These are not simple subjects for anyone to handle, and the ways Truffaut deals with them are heartfelt and passionate; as someone who’s asked similar questions in his own life, I admire Truffaut’s film all the more doe how it asks them.

At one point in the film the house where Davenne stays at is hit by a thunderstorm, and the room he has maintained to honor his wife’s memory catches fire; he must find a new way to preserve her memory. He gets permission to restore an old church, which he will fill with pictures and mementos of “his dead”– the ones he has carried with him in life after their death. It’s a beautiful sight, one of the most memorable in all of my film experiences, but it gets to the heart of the film’s questions, especially when he asks the young widow Cecilia (the character played by Baye) he has come to know to help him maintain it. But their way of honoring them is different, and it’s that tension that drives their relationship to its heartbreaking climax in the church.

Truffaut died six years after this film of a brain tumor; did he know his own life was coming to an end when he made thing film? Is that why he eschewed the autobiographical joy of his earlier films to make this somber work? But “The Green Room” may be more autobiographical than it appears. One of the fundamental qualities of the French New Wave, and particular Truffaut, was its reverence towards the great directors of the past. Without the New Wave, would Orson Welles’s post-“Kane” films be as revered as it is? Would the American crime films of the ’40s and ’50s have been labeled film noir, and become classics? And who can forget Truffaut’s love for Hitchcock, not only in his book-length interview with the master of suspense but also with references he made in his own films? In this consideration, “The Green Room” is just as personal to the director as his earlier, more joyous expressions of love for cinema.