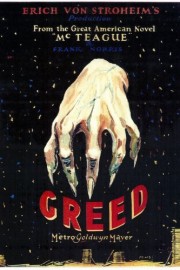

Greed

The history of Erich von Stroheim’s “Greed” is among the most fascinating in cinema. Based on the novel McTeague by Frank Norris, von Stroheim (who aside from being an important early director is arguably better known now for famous performances in Renoir’s “Grand Illusion” and Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard”) created an epic drama that originally ran over nine hours long. For the heads of MGM, this was unacceptable, and the film would eventually be butchered down to 140 minutes, although this version is considered one of the greatest films of all-time. The original version of “Greed” was only screened once, and the edited footage (considered by many the “Holy Grail” of cinema) has been long thought destroyed.

But the 140-minute version isn’t the “Greed” I watched this week. In the ’90s, Turner Classic Movies took a unique approach to film restoration and reconstruction. After discovering not just von Stroheim’s original shooting script (at 330 pages long) but a vaults-worth of production stills, film restorer Rick Schmidlin combined the existing film with the stills (using the script as a guide) to create a four-hour version that has been shown on occasion by TCM. It is this version I watched for my “Movie a Week” screening, and it’s the first time I’ve seen the film at all.

The deeper one gets into the silent era, the one notices how the lack of recorded sound helped and hindered certain genres. Silent comedy, for instance, is still one of the richest of periods for the genre; the masters like Keaton and Chaplin didn’t need dialogue to help tell their delightful and sweet stories. Meanwhile, horror (and fantasy) never had it so good after sound was introduced, as is evident in masterpieces like “Nosferatu,” “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and “Metropolis.” The most challenging of the silent genres is drama; so much of the storytelling relies on personal interaction that the exaggerated physical movements that only added to the moods of comedy and horror dated dramas from the era.

This is where the greats like D.W. Griffith and Erich von Stroheim proved their mastery of cinema. And “Greed” is one of the best at translating the realism of life to the screen. This is a compelling human drama about people, their hopes and dreams, and the circumstances that will make conflict inevitable. “Greed” is the story of a miner’s son (McTeague, played by Gibson Gowland) who turns to dentistry at the beset of his mother and moves to San Francisco. He has a successful practice (although he learned the trade from a quack who strolled into his hometown), and falls in love with Trina (Zasu Pitts) as she sits in his chair. Trina’s original suitor Marcus (Jean Hersholt) is a good friend of McTeague’s, but nonetheless steps aside out of loyalty to his friend. When Trina wins the lottery however, well, we all know what money does to people…

McTeague is an interesting main character. His infatuation with Trina starts when she’s chloroformed for a procedure he’s going to perform. While she’s under, he smells her perfume, and if the title cards are any indication when he’s talking to Marcus later, he might have done more than that while she was under. And then there’s the moment later when he’s buying tickets for the two of them for the theatre. He gets unruly with the box-office cashier when he asks for seats on the right-hand side (away from the drums). When the cashier informs him that seats on the right are next to the drums, he becomes confused and angry. In spite of all this, however, McTeague is a good person at his core. He just wants to live in peace, with Trina, and practice his trade. Unfortunately for him, Trina is a miser, who wants to hold on to her money as much as possible. They still manage to eek out a good living, but when Marcus betrays them both, their life falls on hard times. Needless to say, this isn’t the type of story neither Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg (who ran MGM at the time) wanted to release (certainly not at nine hours) nor audiences in the Roaring Twenties wanted to see– it was too bleak, too subversive, and too real. Of course, those are all of the qualities that make it a classic now.

Throughout the film, we see scenes (recreated by Schmidlin) of Zwerkow (Cesare Gravina), a junkman obsessed with finding the location of gold his partner Maria (Dale Fuller) has teased him with over the years. They serve as an intriguing, sometimes hallucinatory counterpoint to the main plot with McTeague and Trina. For a while, the scenes seem to have no real purpose to the story until we see Trina talking to Maria. Zwerkow’s greed will eventually lead to the death of both him and Maria, just as greed (his own, Trina’s and Marcus’s) will eventually lead to McTeague’s death in Death Valley at a mine. The funny thing about “Greed” is that while the film seems unnecessarily long for how simple the story is, there isn’t anything (at least in the version Schmidlin “restored”) that I would deem necessary to cut. Every scene, every story beat feels essential to von Stroheim’s vision. No one alive has seen the original version of “Greed,” and while it’s hard to imagine sitting through the film for nine hours, it’s equally hard to imagine that maybe von Stroheim’s conceptualization of the story was less gratuitous self-indulgence (the director’s own greed, if you will) and more the only way to bring it to life. Alas, now we’ll never know.

(On a personal note, in an age when I can watch five different cuts of “Blade Runner” and multiple versions of even the most infantile comedies, how is it “Greed,” one of the legendary classics in film history, is still unavailable on DVD? Not that I’m looking to own it anytime soon, but what is TCM waiting for so that film fans can watch both existing versions of von Stroheim’s masterpiece?)