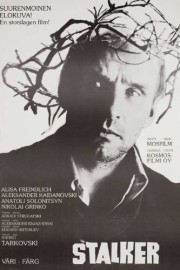

Stalker

**I also wrote about “Stalker” as part of Film for Thought’s “Ultimate Choice” blog on favorite Foreign-Language Films here.

How I first came to see Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 epic “Stalker” is actually an interesting story. Back in September of 1994 I was highly anticipating the video release of Alex Proyas’ “The Crow,” which now stands as my favorite film of all-time. Just before being released a review of the movie and other films by the late actor Brandon Lee was published in Entertainment Weekly, where the reviewer- Glenn Kenny, now writing for Premiere- praised Lee’s haunting performance and Proyas’ visual style, likening some moments to “Andrei Tarkovsky’s detritus-strewn masterwork ‘Stalker.'” It was a little nod, but I remained intrigue by that reference, and tried to look for the film to watch for about 2 1/2 years, until I finally found the film at a local Video Wonderland- shortly before I began working there- in June of 1997 after my last final of my first year at Georgia State.

The film has never left my imagination since, and I immediately began looking to add it to my collection. “Stalker” is one of the most haunting visions (shot in a rich combination of Black & White and Color- a Tarkovsky trademark- by Aleksandr Knyazhinsky) and aural landscapes (courtesy of evocative composition by Eduard Artemyev and sound design by Vladimir Ivanovich Sharun, whom create a truly spellbinding atmosphere) ever put on film, a journey of the belief in something bigger being able to fulfill our innermost dreams in a world of despair and the basic need for happiness in one’s life. It’s a theme- along with longing and devotion towards family (also prevalent- however subtly- in “Stalker”)- that is explored time and again in the best works of Andrei Tarkovsky, the Russian auteur who co-wrote and directed the film.

The son of a famed Russian poet (whose work is quoted often in Tarkovsky’s latter works), Tarkovsky’s the most famous Russian filmmaker since silent great Sergei Eisenstein (whose “Battleship Potemkin” is a film school staple). And yet his name is not nearly as familiar to general movie audiences as other giants in World Cinema such as Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman, both of whom were friends with and great admirers of Tarkovsky’s. Here’s an overview: After making a prize-winning student film- “Steamroller and the Violin”- in 1960, Tarkovsky made waves on the international circuit with his first feature film- 1962’s “Ivan’s Childhood” (better known as “My Name is Ivan” in the US)- as the story of a young boy who becomes a Russian spy during WWII after his family is murdered won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, where Bergman proclaimed, “I felt encouraged and stimulated: someone was expressing what I had always wanted to say without knowing how.” Four years later, Tarkovsky’s second feature- the epic “Andrei Rublev,” about a famed 15th Century icon painter- was suppressed by the Russian government, and not shown outside of the USSR for several years, and even then usually in a censored version. The original director’s cut- which clocks in at a staggering 205 minutes- is now available courtesy of the Criterion Collection on DVD, whereas the censored version- 20 minutes shorter- is only available on VHS. Either way, it’s one of the greatest films I’ve ever seen. In 1972, he adapted Stanislaw Lem’s novel “Solaris” into what many consider the Russian answer to “2001.” It was the only film of his Tarkovsky looked down upon, though it is still quite a fine effort overall. Criterion has announced it will be releasing “Solaris” on DVD in November to coincide with the forthcoming return to the Lem novel- it’s not a remake of this film- by director Steven Soderbergh and star George Clooney, slated for release November 27. After “Solaris” came a highly personal story of childhood memories in 1975, “The Mirror,” followed by “Stalker” in 1979. The film was Tarkovsky’s last in Russia, and in 1983 he filmed another most personal story about family devotion in Italy called “Nostalghia” which won three awards at the Cannes Film Festival (where Tarkovsky was a favorite filmmaker). Finally, in 1986 he made his seventh film, this time in Sweden with many Bergman collaborators, which was about one man’s plea for his family to be spared at the outset of WWIII. “The Sacrifice” was Tarkovsky’s last film, as he had been diagnosed with a brain tumor during the making of it, and died as it was being released on December 28, 1986. He was 54 years old. He’s now regarded as a very popular figure in the arts in Russia, as celebrations- and even the unveiling of a bronze statue in his image- have been going on all year in celebration of his 70th birthday. Most of his films- even “Steamroller”- are available on DVD in the states, or are becoming available on DVD, but are near-impossible to find at the chains. For the curious, mom-and-pop video stores- and Netflix.com- are your best bets. VHS copies are even scarcer, though you can find “Solaris” or “Andrei Rublev” at Blockbuster or Hollywood every once in a while. If you check the TV listings, you may- on occasions- be able to find a broadcast of one or more of his movies on Turner Classic Movies. Maybe Soderbergh’s “Solaris” will get people curious about Tarkovsky’s version, and Tarkovsky in general. One can hope.

If you choose to explore the filmmography of Andrei Tarkovsky, however, a word of caution. Like Kubrick, the beauty of each shot reveals itself through time. Tarkovsky asks us to contemplate every detail (the depth of each shot composed is a wonder to behold, especially in “Nostalghia” and “Stalker”), every moment, every line of dialogue uttered. A family lying in bed. A trip across a desolate Russian valley. The near-endlessness of rolling hills of sand. A young girl staring off across a body of water. Even three guys sitting around a table in a deserted tavern; these scenes in “Stalker”- which could also have been a visual influence on the underrated thriller “The Cell” (in addition to “The Crow”) a couple of years back- has the power to make you think about what the significance- spiritual, emotional, or otherwise- of the scene. It’s not as noticeable in “Childhood” or “Rublev,” but the older he got, the longer his shots lasted, the more personal his stories became, and the more audacious his storytelling became. By the time he made “The Sacrifice,” he was less interested in pandering to the audience than ever before (he was never much for conventional narrative or entertainment anyhow), and more interested in creating a uniquely profound cinematic universe, where awe-inspiring natural visuals and soul-stirring inner journeys are more important than elaborate CG-effects and traditional plot twists. Like in Kubrick, there are few easy answers to every question that’s brought up, but it’s not the conclusions that count, it’s the fact that the questions were asked that matters most. He was probably cinema’s most compelling philosopher, certainly it’s most profound visual poet, and unquestionably one of it’s purest visionaries.

“Stalker” probably represents Tarkovsky’s most compromised vision (more on that later), and yet it remains purely his vision. It’s based on the obscure novel “Roadside Picnic” by Arkady and Boris Strugatzki, who also wrote the adaptation with an uncredited Tarkovsky. The story tells of a Stalker (Aleksandr Kajdanovsky), a man who takes people into a mysterious region known as the Zone, which is rumored to be able to fulfill people’s innermost hopes and dreams. The origin of the mystical power of the Zone is also a thing of rumor, but the possibilities of what the Zone could give a visitor are such that it is heavily guarded, meaning anyone who risks passage is at risk of their lives. The Stalker has been in and out of prison for his “smuggling” of individuals into the Zone, but much to the disapproval of his sad but devoted wife (whose disapproval is as much on their daughter- whose been deformed as a result of the Zone- Monkey’s behalf as it is her own), he has agreed to take two people into the Zone, a Writer (Anatoli Solonitsyn) and a Professor (Nikolai Grinko). Following a well-orchestrated sequence as Stalker, Writer, and Professor make their way through the gates to the Zone (this is where the visual similarities between this and Proyas’ “Crow” are most evident), their journey begins, but not before Stalker must clarify some rules about the Zone, which is said to be a maze of traps. Ways that were safe before are likely no longer safe. The shortest path will usually take the longest time to cross. Straight paths can also be dangerous. The Stalker determines path by way of tossing a nut wrapped with a flag. You can never exit the way you entered. Following these rules (sometimes more often than others), the three make their way to the Room at the Zone’s center. Only there can their hopes be realized. Admittedly, for all the trouble the trio go through to get to the Room, the payoff when they arrive is minimal; but like any great story of discovery, the goal they had in mind is always subordinate to what was experienced along the way.

As in “2001,” dialogue- or rather, the act of hearing people speak- is secondary to telling the story through visions, sound design, and music. But more than “2001” and even “A.I.,” the dialogue does much to define the characters, as well as orient the viewer to the Zone and the film’s universe in general. Stalker- a character of ambiguity, authority, and surprising gravity as played by Kajdanovsky- is a character at home in the Zone. He feels more comfortable here- given the power he has over those he takes into the Zone- than he does with his own wife and daughter. An implication is that the Stalker is nothing more than a con artist, a swindler who plays up the mystery of the Zone, and the promises of wishes granted, taking his “victims” on a wild goose chase, crushing their spirits, and making some money in the process. It’s a credit to the performance that one could guess otherwise, though the ending does discredit the notion of Stalker as a con man. Writer- performed with world-weary grace and boiling emotion by Solonitsyn- is a writer who’s lost the fire and inspiration to write. He’s like the gifted painter in Tarkovsky’s “Rublev” who puts down his brush, only to be inspired again by a truly miraculous human creation, only it’s unsure if the Writer even wants to write anymore at the end. It’s possible he’s accepted his inability to write, and can learn to live without it. If you’re looking for pat answers, don’t bother; the ending leaves it up to your own interpretation. Professor- exceptionally played by Grinko- is the least obvious character of the film. It remains uncertain what his intentions are up until their arrival at the Room, and even then, it still is difficult to determine what he will do until the end.

Like the monolith in “2001,” the origin of the Zone is a mystery to the characters and audience to be solved. The most widely-regarded theory about the Zone in “Stalker” is that a meteorite landed in the region, wiping out the citizens, but leaving a supernatural force behind. On a level of sci-fi, this makes sense; however, a more frightening, realistic notion- one hinted at in the film to a degree- exists as well. It’s not wholly far-fetched to believe that the Zone was created by a nuclear meltdown in the region; at one point the Professor- while talking on the phone- mentions that he’s found “Bunker 4.” Oddly prophetic, as it was the fourth energy block at the Chernobyl power plant in Russia that would explode, resulting in the most notorious nuclear disaster of the Cold War. (Thank you to Nostalghia.com, a most comprehensive Tarkovsky dedication- located at http://www.acs.ucalgary.ca/~tstronds/nostalghia.com/index.html- for the article that points this out.) This would certainly explain the notion of Stalker’s daughter being deformed (as a result of radiation), the excessive military guard surrounding the Zone, the rumor of how those who enter the Zone never come out, and the fact that no meteorite was in fact found in the region. However, Tarkovsky- spiritualist artist he was- leaves open both notions as possibilities while exploring the questions of the power greater than man that the Zone may possess. At one point one of the travelers questions Stalker about whether he has seen a lot of “happy people” in the groups he has lead into the Zone; the Stalker says starkly, “No, because when they leave the Zone, we never meet again.” It’s an interesting answer, but one explained in that the Zone doesn’t grant wishes immediately, and may not grant some at all. It’s not stated that all who come to the Zone get what they wish for, and as you’ll see in “Stalker,” that very much holds true. However, entering the Zone and facing it’s traps and mazes may provide for a need not immediately felt by the traveler. Something much harder to explain, much more difficult to put into words.

The making of “Stalker”- which I actually just learned earlier this summer- also lends itself to a certain degree of mystery. Many people online who have read the book and seen the movie (unlike “A.I.” and “2001,” I can’t claim to be one of them) will easily tell you that the original story of “Roadside Picnic” is very dissimilar to Tarkovsky’s intimate epic (it clocks in at 160 minutes). What they won’t tell you- likely because they don’t know- is why. Originally, Tarkovsky’s intention- as remembered by co-author Arkady Strugatsky- was to follow the book intently. He began shooting- with a different cinematographer, Georgi Rerberg, than who finished the film- supposedly with scarce Kodak stock film that was provided by the worldwide distributor of his films in West Berlin, and at an aspect ratio (2.35:1) widely known in the States as Cinemascope, except being called Sovoscope. How is the aspect ratio important? Check out the next paragraph. Filming on “Stalker” had been going on for about a month when disaster struck- the processing machine at the Mosfilm lab broke down, and the film was unable to be processed, resulting in a loss of quality in picture that made all footage shot up until that time useless. “Officially,” it was a machine malfunction, though Tarkovsky cried foul on part of the Russian film industry, saying they switched film stocks before giving it to him to shoot with. Either way, if Tarkovsky was to complete the film, compromises would have to be made. A dramatically-reduced budget was alotted for the completion of the film, which needed to be rewritten and reimagined to make up for the reduction of financial resources. This is the version of the film that exists, and it is of great testament to Tarkovsky, his collaborators, and the strength of his material that the film works as beautifully as it does. Unfortunately, filming didn’t get any better for the crew (see Nostalghia.com for details), and the location where filming took place was located near a chemical plant, which resulted in allergic reactions, and years later, the deaths of key figures on the film, including Tarkovsky and his wife Larissa.

Bringing “Stalker” to audiences via DVD hasn’t been much easier. The film can be found on VHS through Amazon.com (and every once in a while, Mediaplay or Suncoast), but “Stalker” is one of the last of Tarkovsky’s films (along with “Ivan’s Childhood,” which has put off and on slate by Criterion due to trouble finding correct film elements for an acceptable DVD transfer) to see a U.S. release. Originally it seemed Criterion might release “Stalker” as it has “Rublev,” but found it didn’t have the rights from RusCiCo, the Russian Cinema Council. Regardless, “Stalker” has officially been slated for release as a 2-disc set on October 15 from RusCiCo by way of Image Entertainment. But even this is not without controversy. For one thing, RusCiCo was forced to pull their Region 2 release of “Stalker” when fans showed disdain for the disc’s 5.1 remix of the original mono soundtrack that accompanied the film. They soon re-released it with both 5.1 and mono sound options available, both of which will be on the Image release. Where this edition brings pause to fans of the film is in its video transfer, which is formatted at 2.35:1, or the original format that was intended for the film (it should be noted though Tarkovsky- though a master at widescreen formats- was not a fan of this ratio, and was forced to use it for “Rublev” and “Solaris”). Now, if you look up the film on the Internet Movie Database, you’ll see the film is listed as being shot at a ratio of 1.37:1, which is essentially equivalent to what we call “full frame” (1.33:1), which is your standard TV size. Isn’t this a distortion of the film? Yes and no. Yes in that it does in fact represent something the filmmaker didn’t intend, but no in that it doesn’t alter the information in each from as you might think. You see, when Tarkovsky was forced to reshoot, a framing system was used called Universal Frame Format, and bottom line of it is, any framing ratio (2.35:1, 1.33:1, 1.37:1, 1.78:1) can be extracted from a negative print using this system, meaning an acceptable widescreen presentation can be created to suit any desired presentation. In other words, the closer to “TV ratio” (1.33:1) you get, the more you see of the picture. In other words, the VHS copy of “Stalker” I own will preserve the intended vision of the film more than this DVD. Is it likely this one will be reissued in response to criticism from fans as the Region 2 was? Only if Criterion can get their hands on it, and right now, that’s not looking too good. Just another example of a great film not getting the respect it deserves on home video.

One final thing about “Stalker” before I conclude. As mentioned before, this was Tarkovsky’s final film made in his homeland of Russia. At the end of the film, Stalker’s wife- looking directly into the camera- begins an extended and moving monologue on the sacrifices of life with Stalker and their daughter. When looked at in respect to Tarkovsky’s career, his career after “Stalker,” and- if you’re familiar with the excellent documentary “Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky” shot during filming of “The Sacrifice”- Tarkovsky himself, one gets the feeling that through her, Tarkovsky is expressing his own beliefs on the sacrifices and tradeoffs of being an artist, one interested more in deeply spiritual themes than government propaganda, in Communist Russia. When you watch, think about, and experience “Stalker” with that knowledge, it’s hard not to rate Tarkovsky as one of the most personal filmmakers of our time, and all-time.