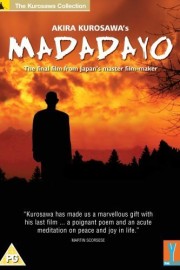

Madadayo

While certainly not a landmark like many of his earlier films, Akira Kurosawa’s final film, “Madadayo,” has lingered long in my memory, and after having seen it again, stands as one of my favorites of the filmmaker’s long career. There’s a joy that comes through in the story- and storytelling- that is of a man who feels as though he has lived his life well, is proud of all he has accomplished, and is just about ready to make one final journey away from the stresses of life on Earth. Made in 1993, five years before his death, “Madadayo” puts on display a master still entranced by his art, but content enough to put it aside for the peace of living well the final years of his life.

In a way, this is very much what the movie is about. At the start of the film, we are in a classroom, it is in 1940s Japan. A professor (Tatsuo Matsumura) is announcing his retirement to his students, whom have been inspired by him so much over the years, along with many others. Thinking about the film before watching it again, it seems very much like “Mr. Holland’s Opus” would have been had it followed Mr. Holland and his students after his retirement, as the professor and his wife are befriended by a handful of his students in the years after his retirement, helping him when needed, and laughing with him when it is the way to best serve him. Maybe an unfair comparison to some- comparing Kurosawa to a Disney inspirational drama- but as someone who’s been consistently entertained and inspired by “Opus” over the years, I find it fitting to compare it to this film in this respect. Plus, it’s my review, so I’ll make comparisons as I see fit.

There’s not much else to the story as what I’ve outlined in the preceding paragraph. The title is translated as meaning, “not yet,” and comes from the annual party the Professor’s students have for him to celebrate his birthday- the students ask, “Maadha kai? (Are you ready?),” to which the professor replies, “Madadayo! (Not Yet!” These parties- we only see the first one and the last one- are joyous in their execution, yet also simple in their staging, not an easy to do with such crowds. The first one in particular is memorable for the student who, when all of them get up to talk about the professor and reminisce, spends the remainder of the party on his speech until all who are around are the professor, the student, and the professor’s doctor (or so we’d like to think).

Kurosawa is best known for his samurai epics like “Seven Samurai,” “Yojimbo,” “Ran,” and “The Hidden Forest,” but “Madadayo” shares much in common with his lesser-known masterpiece “Ikiru,” also about an old man who finds satisfaction in the face of death. My review of that film is to come in the future, but watching both it’s hard not to see how well they compliment one another in the very different ways they look at mortality and the ways people inspire those around them. We never see the professor teach a single student, but we feel throughout the film, in the ways his students help him, how inspiring he was in spite of that. They build him a new house after his is destroyed by the air raids. They visit him in good times and bad times, lifting his spirits and enjoying a drink with him like old times. Even testing his fool-proof burglar-protection system in an ingenious sequence at the beginning too fun to see unfold to give away here.

Most moving is his student’s devotion, however, when a stray cat he and his wife have come to adopt named Nora goes missing. Professor is distraught over the loss. His students set up teams to search, and pass out leaflets to children in the area and pursue leads to no avail (though Kurosawa gives us glimpses of the cat, one implying what might have happened, one intended to be the dream of the professor). The cat never returns, but life has a funny way of restoring balance sometimes.

What’s remarkable in the film is, in effect, how little actually happens in the film. Kurosawa captures so precisely a life devoid of any financial purpose- the film is really a series of vignettes more than a straight narrative- and any purpose beyond simply existing from day to day, occasionally with something to pass the time, that watching the film again, I was reminded of my time at home before I was able to go back to work after getting out of the hospital. Of course, there were things to do on my end, and I did have a purpose to get myself healthy again, but there were times of blissful boredom, when the simple pleasures could be taken in without a worry in the world. Of course, there were other times when I wasn’t content to be alone, as when the Professor’s students must cut a visit short- his loneliness is palpable. Still, that was just for a time, and the Professor’s students will be back to visit another day, as my friends were when I was away.

Movies like “Madadayo” are rarely done for the sake of just making a movie- there’s something more the filmmaker wants to express. One thing that seemed very evident after first watching the film was the sense that Kurosawa had made a film thanking the people he’d inspired over the years for their support in his later years, when money and distribution was not easy for the filmmaker to come by. Filmmakers like George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, who financed his 1980 film “Kagemusha” Like producer Serge Silberman, the French financier of several later Bunuel films who found the money for Kurosawa’s definitive samurai epic “Ran,” inspired by “King Lear.” Like Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, the former whom provided international distribution for his underrated 1990 work “Dreams,” the latter whom appeared in one of the film’s segments as Vincent Van Gogh. Like Richard Gere, who appeared in the director’s next-to-last film “Rhapsody in August.” All of these filmmakers were inspired by Kurosawa in some way over the years, but whereas most inspired by the director simply rehashed and reworked his work for their own devices, these people- more than anyone else- helped the great director continue what he loved, not just paying respect to it in their own work (which they did, no doubt). Is it hard to imagine, then, that all Kurosawa really wanted to say in “Madadayo” was simply, “thank you,” to some of his most devoted students?