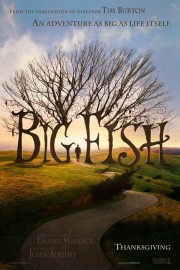

Big Fish

In a just moviegoing world, this is the film that would solidify director Tim Burton as a master storyteller. Don’t mistake “Big Fish” for a “Forrest Gump”-esque tale of an improbable life- it’s too down-to-earth for that. Don’t mistake it for a tribute to a liar’s manipulation- it’s too moving for that (and that’s too simple a meaning for such a slyly-layered story). And don’t mistake it for another Burton freak show (the man did the first two “Batmans,” “Edward Scissorhands,” and “Sleepy Hollow”), though it includes giants, witches, werewolves, and mermaids- it’s too emotionally-diverse- as all of Burton’s films have had a knack of being- for that.

“Big Fish” is an ode to life. Not the life we lead, but the life we remember. Not just the person whose life is remembered, but how those he touched in life remember it. How the fantastic is accepted over the truth. How the imagination of a dreamer inspires the most grounded of a realist. And how in the telling of a story, the manner of the storytelling defines the teller, and shapes their image in the listener.

But in a sense, that’s all of Burton’s films (his best films certainly- “Ed Wood,” “Edward Scissorhands,” “Sleepy Hollow”- which “Big Fish” shares company with). But only in “Big Fish” have these ideas been brought to the forefront with such subtlety and poetry in a Burton film. His style is less flamboyant than usual, but his passion for the story- based on the book by Daniel Wallace- remains undeniable- in personal meaning to Burton, only “Ed Wood,” “Scissorhands,” and the Burton-produced (and inspired) “The Nightmare Before Christmas” come close.

Scripted by John August, making amends for the dreadful “Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle” with a script of nuance and intelligence, “Big Fish” is the story of Edward Bloom, a man dying of cancer with a knack for tall tales, exaggerating the truth of his own life with hard-to-swallow tales of working at the circus, hidden towns, witches that- if you look them in the eye- will show you your future, dealing with giants and haunted forests, catching fish with wedding rings, and bank robberies with famous poets. Bloom is played in his elder years by Albert Finney (“Miller’s Crossing,” “Erin Brockovich”) with robust energy and feeling, and in his mythic youth by Ewan McGregor with boundless charisma and wit. People love the tales his tells, for the most part. His son Will, a just-the-facts reporter (played by “Almost Famous'” Billy Crudup with just the right amount of emotional distance and frustration), has never bought into them, and hasn’t spoken to his father since he told one at his wedding reception three years. Now, with his father dying, Will comes home- at the insistance of his mother Sandra (played by “Matchstick Men’s” delightful Alison Lohman in her idealized youth, and by Oscar-winner Jessica Lange, who brings touching gravity and heart to the older Sandra, especially in a scene where she shares a moment of beautiful intimacy with Edward in a bathtub)- hoping to get the truth, and not just another fantastic story.

If you think you know how it’ll end, you’re probably right, but like any great story, it’s not where you end up, it’s how you get there. That’s what makes “Big Fish”- scored with the striking emotional beauty he’s never been given credit for (and flourishes of his trademark ethereal oddness) by Burton’s frequent collaborator Danny Elfman (“Fish” is one of his best scores)- one for the ages. As much as I’ve enjoyed “Forrest Gump” over the years, I’ve come to find a flaw in the fact that despite all of the experiences Forrest has, he remains unchanged, and is none the smarter. Some call it a triumph of the human spirit; it’s more like a triumph of the uninformed mind to accept the way things are. That Edward twists his story- or does he?; the beautifully-realized final frames suggest either- is a front against the latter and the former; instead, Edward’s tales are a triumph of the imagination. That he feels he must spin unbelievable yarns to give his life meaning is a tragedy I suppose; afterall, should a regular life need enhancing to be memorable? Most would say no, and most would say that what Edward does achieve in life- marrying the woman of his dreams, having a child, touching the people he meets- would be worthy of rememberance.

So why flourish the truth with fantasy? Because it’s our passions that define us; for Edward (and Burton), it’s for fantastical storytelling that pays tribute to the feelings of the moment, not the reality of it. No place else in “Big Fish” is this truer than at its’ end, when Will finally understands his father, and doesn’t just write the conclusion to his father’s whale of a tale, but witnesses it in a coda to his father’s life fully grounded in the factual reality he’s always accepted, but hints at the fantasy he’s always been told by his father. In the end, Will comes to realize- as the audience does- that whether the story of one’s life is completely real is beside the point- what’s important is that he was a small part of it.