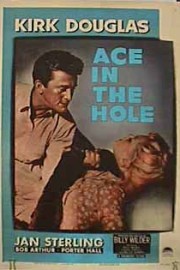

Ace in the Hole

Billy Wilder had a particular gift in his movies of not letting anyone off the hook when it came to his savage humor. He was uncompromising in his ability to take on all sides, even if it was the person was the protagonist in his film, whether it’s the James Cagney’s Coca-Cola executive in “One, Two, Three”; the fading silent film star of his “Sunset Blvd.”; or Kirk Douglas’s unscrupulous newsman in “Ace in the Hole.” The film was forgotten for a while after it failed at the box-office, and was retitled “The Big Carnival,” but it’s been rediscovered thanks to a 2007 Criterion Collection release, and rightfully taken it’s place among the greatest films in Wilder’s career.

Douglas plays Chuck Tatum, a reporter in between jobs with the big-city papers (11 of whom have fired him) who finds himself stranded in Albuquerque when his car breaks down. He walks into the office of the local newspaper, which has a needlepoint hanging up that says, “Tell the Truth.” He pitches himself to the editor, and gets a job, although a year later, he’s still waiting for his big break. He finds it when he comes across the story of a man trapped in a mine. He sees an opportunity: while he was originally in town for a small-town competition, the story of a husband fighting for his life, trapped in a mine, is better copy, and a chance to get back on top. He sets himself up as the exclusive reporter on the case, and does what he can to stretch out the rescue as long as he can. It’s great human interest, until reality sets in about the consequences of the miner, Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), and his chances. By that point, though, the story has taken on a circus atmosphere, with thousands of people gathered to get any bit of news, to pray for Leo, and to show support. Chuck’s career has gotten a second wind, but at what cost?

Billy Wilder takes no prisoners in this movie. Chuck Tatum is one of his most savage characters. He has no scruples whatsoever, and yet, he has a way of ingratiating himself with people that makes it impossible for people not to give him exactly what he wants. Whether it’s Leo’s wife (Jan Sterling) or his cameraman (Robert Arthur), the local sheriff (Ray Teal) or his editor at the paper (Porter Hall), you can sense that everybody sees the con behind Tatum’s words, but they don’t dare call him out on it, and they can’t because he’s too damn charismatic. That’s the secret of Kirk Douglas’s performance, which is brilliantly shaded, with equal parts dark humor and wicked seriousness to go along with the sharp manipulator he proves himself to be. No one questions his motives about why he’s so invested in this story, in Leo, although some hint at noting that something isn’t quite on the level with Chuck’s motivations is seen by all. Some are concerned, but others (like Leo’s wife and the sheriff) play into it for their own desires. As I said, Wilder (who co-wrote the terrific screenplay with Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman) doesn’t let anyone off the hook, though Chuck gets the brunt of his sharp wit, leading to an ending that results in what is known as “movie justice.” No need to feel sorry for him– he had it coming.

It’s interesting that I ended up doing reviews and screenings of this film and Ron Howard’s “The Paper” in back-to-back “Movie a Week” blogs. Both films take on the integrity of journalists and the responsibility towards the truth that must take a front seat to what increases circulation. Howard’s film is much more optimistic than Wilder’s, but one look at the filmmographies of both filmmakers makes that an obvious call. Howard is more hopeful that ultimately, the right path will be taken. Wilder, a refuge from Nazism, knows that man’s heart can be a dark, selfish place, and greed wins out more often than it should. His great balancing act in his films was to show that basic idea in the context of a film that could also be entertaining for a wide part of the audience. “Ace in the Hole” didn’t quite achieve that when it first came out, but because of the people who saw it, loved it, and would reference it over the years (such as Steven Spielberg and “The Sugarland Express” and a great third season “Simpsons” episode, “Radio Bart), the legacy of the film allowed for it to be rediscovered as the visceral sucker punch to journalistic standards it stands as. It’s just as important a message as it ever was, and like a lot of other Wilder films, it is a masterpiece.