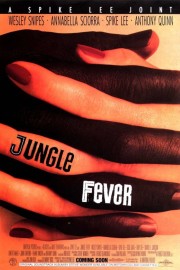

Jungle Fever

Though I’ve respected Spike Lee’s collective body of work I’ve seen over the years, I regretfully am late to the game for some of his most famous films. “Jungle Fever” is one such film, and it’s definitely got the best, and worst, of why Lee is one of the most vital, vibrant filmmakers of the past 30 years.

Over the years, one of the things that has become clear about Spike Lee, even in some of his best films, is that he deals a lot with stereotypes. About black people. About white people. About people in general. About life. The reactions the characters have when the affair Flipper (Wesley Snipes) and Angie (Annabella Sciorra) is revealed are predictably outrageous, and outraged; neither race is happy about it. Yes, Lee deals with stereotypes and cliches, but they come from a very real place; all you have to do is a quick Google search, and you’ll see that anything Lee is saying is pretty spot-on. We may think we’ve evolved when it comes to racism and race relations, but 23 years later, “Jungle Fever” seems just as controversial and provocative as it must have been then. If it were released today, I have no doubt you’d see some of the most bigoted and racist reactions Twitter and the internet has to offer, and that’s saying something. Even the worst reactions, though, let us see that Lee strikes a nerve with his films, and that’s always a good thing, because it means that he gets people thinking about what he says. Some of us just might care to really consider, and learn, from it than others, though.

The title, introduced into the lexicon by this film, refers to sexual attraction between the races. It’s that attraction that propels the film when Flipper, a successful architect and loving husband and wife, has an affair with Angie, a temp secretary who just started as his office, and their lives turn upside down. They are outcasts in their own lives; their families shun them, their friends, though supportive, can only support them so far, and when they’re out in public together, misunderstandings lead to potential tragedies, such as when playful roughhousing leads to a confrontation with the police. Things are going well, but when push comes to shove, do they love each other? Is it just a phase? Is it just lust? Is it about the “forbidden fruit” of being with someone from a different color? That’s a question neither of them ponder until things are on the ropes. Flipper thinks it’s all about color, but for Angie, it feels like, maybe, it was more than that, but even she seems to want to get back together with Paulie (John Turturro), her longtime boyfriend, and it definitely feels like Flipper wants to make things work with Drew (Lonette McKee), at least for the sake of their daughter. By the end, their time together has ended, less because they both want it to, and more because that just seems like it’s gone as far as it can in the confines of this film. I’m not going to say that I’d like this film to be longer, but I will say I wish Lee had gone further to really delve deep into the issues he raises.

If the film has one drawback, it’s that Lee’s screenplay gives a lot of time to storylines and characters apart from Flipper and Angie. That sounds like an odd complaint, especially considering how little a lot of films even delve into the supporting characters, but in this case, it seems to distract from the central story. We get a lot of familial tension with Flipper’s parents (played by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee) and his brother (Samuel L. Jackson), and it’s a rich vein for drama to be sure– Davis’s fundamentalist baptist preacher has a great deal to say about Flipper’s transgressions and Jackson’s Gator, who has a severe drug problem, while Dee’s mother is all love and forgiveness (and all three are stellar) –that would make a fascinating film in it’s own right, but it stops what seems to be the main story between Flipper and Angie in it’s tracks, and, except for an awkward family dinner between the couple and the parents, doesn’t have much to offer it. And the story of Paulie, a kind-hearted young man who helps his father out, and takes his breakup with Angie in stride (more stride than his friends and father do), is another compelling storythread worthy of a film in it’s own right, but again, it doesn’t really contribute much to Flipper and Angie’s story. That lack of focus is both laudable (because it means Lee is seeing a bigger picture) and frustrating (because it’s a little “too big” a picture for what starts out as an intimate love story) for this viewer, who loves it when Lee sets his eyes on a specific target, and tackles it head on.

As a whole, though, “Jungle Fever” is a lovely effort from a filmmaker whose work is always fascinating, even when it’s deeply flawed. With a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder and composer Terence Blanchard that captures the tone and pain of the film beautifully, “Jungle Fever” has some entertainment value, as well, but it’s the larger social issues it raises that pierce through the film’s sometimes-padded storyline, and gets to the heart of who we at our best, and our worst, a common subject for the filmmaker.