Inherit the Wind

It goes without saying that I’ve never been as eloquent a writer as the late Roger Ebert, but that feels even truer when I watch one of his “Great Movies” to review on my own. That feels all the more accurate when it comes to “Inherit the Wind,” Stanley Kramer’s 1960 adaptation of a stage play which dramatizes the Scopes Trial of 1925. Ebert wrote beautifully about Darwin’s theory of evolution, and in this case, that writing was woven into his love of film in a wonderful way in his 2006 review of Kramer’s review.

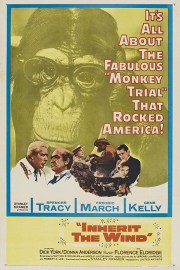

In “Wind,” the names are changed, but the story is so obviously that of the Scopes Trial that it might as well just have said “based on a true story.” That trial happened when a science teacher named John T. Scopes was arrested for violating a state law prohibiting the teaching of evolution in schools. For lawmakers, the Bible was the literal truth, and thus, evolution, and Darwin, was an attack on that truth. To prosecute Scopes, William Jennings Bryan, a three-time Presidential nominee and fundamentalist Christian, came to town, although he met his match in Clarence Darrow, who defended Scopes. In the play (and film), Darrow is Henry Drummond, played by Spencer Tracy, and Bryan is Matthew Harrison Brady, played by Fredric March, while Scopes becomes Bertram T. Cates (Dick York), who is in love with a preacher’s daughter (Donna Anderson). Talk about having a difficult relationship with your potential father-in-law.

This is the first time I’ve seen the film, but I’ve read Ebert’s review several times. That colors one’s opinion when you watch a film for the first time, but it goes without saying that he had pretty good taste. From there, it’s up to the film to work it’s magic, and move you on it’s own terms. “Inherit the Wind” is a film that does just that. Images are not as interesting to Kramer as ideas are, and “Wind” has some juicy ones. The core one in the film is, of course, the divide between people who believe in the literal truth of the Bible, and think the Earth (and man) was created more or less as they are, and those who look at evolution, and see a greater understanding of the world, and where we came from. Almost 90 years after the Scopes trial, that divide is still prevalent in American culture, and even though we learn more about evolution through scientific exploration all the time, it seems to grow wider all the time. In that conflict, the film may come down on the side of evolution, and Drummond, but Kramer presents as even-handed an argument between the two as anyone can offer.

There’s more to the film than just the debate about the origins of man, though; if that was all that mattered, the subject would be better handled by a documentary. The love story between Cates and Robin, the preacher’s daughter, is a weak point in the film, but it serves to bring a personal tension between religious belief vs. scientific thought when the daughter is caught between her love for Cates and the bone-deep conviction of her father (Claude Akins). That’s never more true when Brady calls Robin to the stand, and pushes her to the point of tears, and betraying her love. When Cates implores Drummond to let Robin go before he can cross-examine her, he seems to have written his own fate, especially after Drummond’s scientist witnesses are thrown out because, according to the judge (Harry Morgan), their thoughts on evolution have no baring on the trial at hand. The next day, out of options, Drummond does something audacious, and calls Brady to the stand to testify on the Bible, just as Darrow did Bryan during the Scopes trial. What transpires at that point is a showdown between reason and blind faith which Tracy and March play with furious intensity and power that brings everything the film has set up to a head in an emotional, and exhausting, summation that makes the actual verdict, and all that happens afterwards, feel anticlimactic by comparison.

The courtroom drama was a tried and true formula for Hollywood by the time “Inherit the Wind” was released, having been established effortlessly by Sidney Lumet’s “12 Angry Men” a few years earlier. It’s only grown in use, to the point of cliche, ever since, but Kramer’s film, flawlessly acted, remains a powerful, relevant fixture at the peak of the genre. Some of the reason for that is, probably, how the ideas and conflicts it examines are still important now, but even when/if the debate of creationism vs. evolution dies down, I have a feeling “Inherit the Wind” will have no trouble living on as a evocation of the passions the dispute inflames. That, above all, is the definition of a “Great Movie,” and as always, Roger Ebert knew how to pick them.