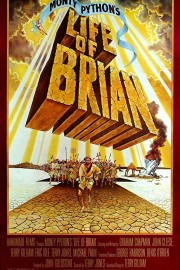

Monty Python’s Life of Brian

In light of the recent uproar in the Middle East surrounding an inflammatory (and, from what I’ve heard, poorly-produced) film about the prophet Muhammad that lead to the deaths of four Americans in Libya, I thought it was time to look at “Monty Python’s Life of Brian.” The Python’s had a wicked hard time getting this made, what with people perceiving it as an attack on their Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. Of course, so clueless are his followers at times that they didn’t realize that the British bad boys were really taking on those that were their greatest critics.

Watching it now, I find it impossible for anyone to find “Life of Brian” objectionable in any way towards Christ at all. Yes, he DOES make an appearance, but his story is along the edges. The real star of the film is Brian (Graham Chapman), a Jewish-Roman boy born in the manger next to Jesus. After the three wise men accidentally pop up at Brian’s manger instead, it isn’t until 33 AD that we catch up with him again. It’s at the Sermon on the Mount, where Brian and his mother (Terry Jones) are on the fringes of the crowd, unable to hear Christ speak (“I think he said, ‘Blessed are the cheesemakers.'”), when we see both Brian and Jesus again. We can’t hear much of what Jesus is saying, either, as Brian has gotten into a shouting match with a few other people before Brian and his mother give up, and go to a stoning.

This is quite a look at First Century Judea. The stoning is the film’s first, great set piece, as the official in charge of the stoning (John Cleese) gets stoned himself by an overzealous crowd. It’s a slow-burn sequence that goes exactly where you expect it to when the Python’s set it up. Not long after, Brian gets in league with the People’s Front of Judea, a revolutionary group that hates the Romans almost as much as they do the Judean’s People’s Front. He passes their first test in painting “Romans Go Home” on the wall of the palace, but not without a grammar lesson from the guards first. Unfortunately, Brian finds himself captured by a lisping Pontius Pilate (Michael Palin), although he manages to escape with some, shall I say, “devine intervention” (okay, a spaceship comes at an opportune time). This leads him to the ultimate crux of the film, when he is mistaken as the Messiah by a group of people who seem to blindly follow anyone. (As one person says, “I should know, I’ve followed a few in my time.”)

By this time in the film, it should be obvious to anyone that this isn’t making fun of Christ at all; in fact, his message is taken quite seriously. (“I think he said, ‘Blessed are the meek.’ That’s nice, they always have such a hard time.”) That being said, a film like this’s biggest critics usually have never seen the film, so it makes sense that they don’t understand this obvious, not-so-subtle nuance. But as we see Brian try and escape this Messiah Complex people thrust upon him, the more biting the Python’s get in satirizing the ridiculousness of the crowd following him: the en-masse call and responses (“We must learn to think for ourselves!” “We are ALL different!”); the idea of miracles that aren’t there (like the man who took a vow of silence 18 years ago, only to break it when Brian is running from his “followers”); and the notion that a gourd Brian owns (inadvertently), or a shoe he loses, is a “holy message.” This is silliness of the highest order, and a sign, to this fan of the Python’s, that their message of always looking on the bright side of life (as sung at the end in Eric Idle’s iconic crucifixion musical number) comes from a higher authority than any of us.