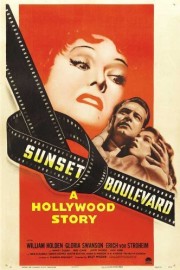

Sunset Blvd.

In his biting screenplay for “Sunset Blvd.” with Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman Jr., Billy Wilder pours so much acid on Hollywood’s image of itself that it’s amazing that the director continued to thrive in the business afterwards, and yet, still ahead of him were comedy classics “Some Like It Hot,” “One Two Three,” and the Oscar winner, “The Apartment.” Wilder’s film is one of the great movies about Hollywood ever made, and it’s greatness lies in the details that Wilder brought to the film, with so many industry people playing themselves, and so many others brought up in name.

However, “Sunset Blvd.” isn’t like other movies about the business, such as Altman’s “The Player,” “The Bad and the Beautiful,” and “Ed Wood.” Wilder gives the film the distinct feel of film noir by having the story narrated by Joe Gillis, the out-of-work screenwriter played by William Holden. Of course, Wilder knew that type of story well, having already directed a classic in the genre (not yet named) in “Double Indemnity,” and the atmosphere of desperation and darkness in noir provides a unique perspective on the subjects of “Sunset.”

When Gillis pulls into the garage of a run-down Hollywood mansion to escape creditors looking to take his car away, he has no idea what he is getting into. The mansion he pulls into belongs to one Norma Desmond, a silent movie star who didn’t make the transition into talkies because…she didn’t believe in them; after all, they didn’t need dialogue, just looks. (Kind of sounds like the main character in the current Best Picture front-runner, “The Artist,” doesn’t it?) There she lives with her faithful butler, Max Von Mayerling, who was once a silent director, as well as one of Desmond’s ex-husbands, screening her old movies and dreaming of a return to the screen for Norma. Joe becomes trapped, as Norma tempts him to live at the house, on Sunset Blvd., and work on a screenplay for her. It’s not long before the situation gets infinitely more complicated, which is why the first time we see Joe, he is face down in Norma’s pool, narrating his own story from the afterlife.

This is just a great film. I can’t put it any plainer than that. On the one hand, it’s a Hollywood freak show about the delusions of an actress obsessed with the idea that it’s only a matter of time before she’s back on top, and the servant who loves her too much to let her see the truth. On the other hand, it’s a love letter to the romance of the movies: the glamor; the idealism; the creative spirit; and the desire to just be loved by an audience. And then, there are the romantic tragedies that drive the narrative: the love Max, who discovered her at 16, and never got over her, feels for Norma; the love Norma feels for Joe, who gives in to the delusion because Norma gives her a comfortable living; and finally, the love that grows between Joe and Betty (Nancy Olson), a copy girl at Paramount who helps goad Joe’s creative juices. Unfortunately, the last one, the most natural one, is doomed, because it gets in the way of Norma’s delusions of grandeur, of the life she had before the camera’s stopped rolling.

So many things come into convergence to make this film the masterpiece it is, from the writing and directing of Wilder to the Gothic designs of the art direction to the haunting music by Franz Waxman to the authenticity Wilder and co. brought to this vision of Hollywood in the early ’50s (yes, that really is Cecil B. DeMille on the set of his epic, “Samson and Delilah”). In the end, though, the film comes down to the performances. Holden does a great job as Gillis, and makes the character’s unlikely willingness to be held captive believable, but the film’s real heart comes from Gloria Swanson as Norma (in one of the great performances in movie history), and Erich von Stroheim, the great silent film director, as Max. Because these two are playing heightened versions of themselves, the pain we feel for both of them is very real, as they live a life that passed them by a long time ago. Still, it’s hard not to feel anything short of rapturous excitement at the end, as the cameras roll, and Norma makes her way down the stairs, ready for her close-up once again. Regardless of how you feel about everything that came before, you have to hand it to Wilder– he definitely knew how to end a movie.